is performance art outdated in a dystopia?

performance art, sincerity, and dirtbag tendencies

This essay is the final instalment of Digitally Altar-ed, a four-part series dissecting the elements of art, social media, and collective consciousness that we choose to worship in the all-consuming digital realm. Each essay can be read independently, but together they capture a growing, dangerously misplaced idolatry driven by our engagement with the internet. You can read the other pieces here when released and subscribe to receive them in your inbox.

What happens when you put a woman in a room and instruct strangers to do whatever they want to her? We think we know the answer. The reality is worse than we could predict. Not necessarily in its specifics- at a certain level of depravity there are so few expectations that nothing remains surprising. But because to watch it unfold, seeing it happen with your own eyes, is to breach your own expectations of safety. Of humanity.

“Instructions.

There are 72 objects on the table that one can use on me as desired.

Performance.

I am the object.

During this period I take full responsibility.”

- Rhythm 0, Marina Abramović (1974)

Marina Abramović’s Rhythm 0 (1974) was six-hours of organic horror. In a recording of the event that’s only a fraction of the length, I watch the piece take shape. I see Abramović position herself by a table of tools. The crowd are told that the piece has begun, and that they should start to use the instruments however they want. She is groped. After three hours, her clothes are sliced off. Her neck is cut into, and her blood drunk from it. I watch her silently cry in fear, in a feeling of complete disconnect from her own body, with someone else’s hand reaching up to wipe away the tear tracks. I cry with her. She’s learning that she was never safe to begin with, and so am I. She’s realising that the only thing holding back those who are violating her was the opportunity. In the gallery, back in my real world, a man walks past me and sees her peril on the screen. He watches around thirty seconds of the gut-wrenching film: a half-naked Abramović stands in a picture of passivity, a gun is held to her head, and her own finger twisted around the trigger. The man chuckles to himself, quietly, and moves on.

I’m left by the table of objects that were used those 50 years ago. Sick, mouth wide, staring at the space where he stood.

This time last year I saw the Marina Abramović retrospective at the Royal Academy, celebrating the impressive career of the “grandmother of performance art”. Not only were many films of her performance art pieces displayed, several were recreated. Imponderabilia: to pass through a doorway between two of the rooms, you could walk between two people, naked, who stood silently for hours. Luminosity: an artist sits on a bike seat mounted high on a wall, naked, for 30 minutes. The House with the Ocean View: an artist lives for 12 days in a constructed ‘house’ within the gallery, alone, yet on display.

The huge success of the exhibition, which likely contributed to the spike in her notoriety early this year, demonstrates a continued thirst for performance art today. Though we might hear less about current performance artists, the field is still active. But can it have a space in the art and media space now? Is it even possible to access that essence of impact in our digitally-obsessed world?

Though the term ‘performance art’ was widely adopted in the 70s, art dating back to the 1910s can be included in its scope, including pieces from the Dada movement (responding to the horrors of World War One) such as those of Marcel Duchamp. Performance art in the way we view it now includes photographs or videos of the piece in action, consisting of an active, live, human piece of some form.

Present-day performance artists enact their work in an often referential sense, in a manner that often harks back to previous iterations- or, at least, what we imagine them to have been like. Anne Imhoff’s 2017 piece Faust, in which performers encased in glass walls and floors are observed “singing, headbanging, dancing, wrestling, playing dirgeful music, climbing up walls, and perching on pedestals as living sculptures” (Elizabeth Fullerton, for ARTnews, 2017), won the Golden Lion prize. It’s immediately reminiscent of Carolee Schneemann’s focus on kineticism, such as her iconic Meat Joy (1964) in which naked performers writhed in raw fish, meat, poultry, and paint. Interestingly, Schneemann was awarded the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement in the same year as Imhoff’s win. Donna Huanca’s immersive sonic experiences paired with her painting of “models” in various colours in OBSIDIAN LADDER (2019) conjure the brush women of Yves Klein’s Anthropometries (1960), and are intended to evoke the ‘happenings’ of 60s New York City, in which art would be a transient experience for a gallery full of people, rather than a painting on a wall. Whether the similarities are purely intentional or simply because there’s most art can be traced back to historical pieces aside, as long as people still have things to y, performance art will still be happening somewhere.

Many of the most prolific performance artists were women, despite the art world being so dominated by men. Where performance art challenges the real, it lends itself to resistance.

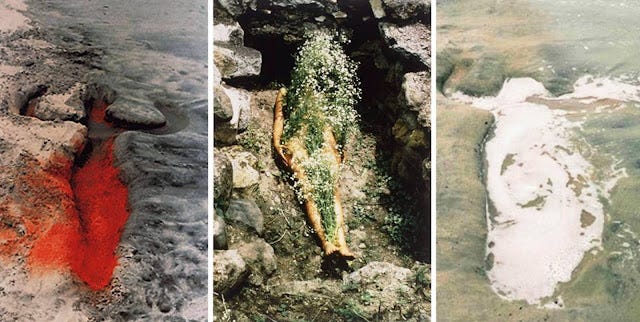

“Performance can be fuelled by rage in a way that painting and sculpture cannot.” - Judy Chicago

Carolee Schneemann noted that, until the work of herself and her peers, there was no space for performance art by women, who instead had to create “clearly in the traditions and pathways hacked out by the men”. One of the most poignant voices in performance art was Ana Mendieta, who refused to allow victims of rape and femicide to be forgotten through her provocative pieces. This included works like Moffit Building Piece (1973), in which rags and animal blood were poured across pavements and left for passers by to find. Her 1975 film Silueta sangrienta (Bloody Silhouette) saw Mendieta’s refrain of her own body’s outline interspersed with the same shape made of blood. Her work not only challenged the acceptance of gendered violence, but also explored her experience as a Cuban woman in the US. She dedicated her art to creating visceral portrayals of the reality of violence against women, until her death, aged just 36 years old. Though he was acquitted, it is thought widely that Mendieta’s own husband, artist Carl Andre, killed her, by pushing her out of a window during an argument.

Ana Mendieta’s legacy lives on today in artists of all media, including performance artists. Jasmeen Patheja’s Blank Noise (2003) project in India drew attention to the fear women face in public spaces and the restrictions they put on themselves, and her exhibition of clothes women had been wearing when they were assaulted (I Never Ask For It, 2005) garnered huge attention. The group Women, Life, Freedom create huge installation pieces in solidarity with Iranian protesters who seek a future free from violence, including assembling 250 participants behind an image of the face of Nika Shahkarami, who was killed shortly after protesting for women’s rights. The participants form Shahkarami’s hair, raising and waving their arms to show its free movement.

“performance is not (and never was) a medium, not something that an artwork can be but rather a set of questions and concerns about how art relates to people and the wider social world” - Jonah Westerman, art theorist, 2016

Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964) could be seen as having set the stage for Rhythm 0. In this piece, designed to embody Ono’s exoticisation and experience of othering in her body, the audience take scissors to her clothes and cut sections away. Whether it was as a Japanese woman fetishized in London and New York, or as a woman who identifies as American being stripped of her identity in Japan, the sensitivity of the piece is layered. At the beginning, they are tame, taking small pieces with them as instructed, particularly the women. Some others become greedy. You can see the moment where the feeling of power overtakes them, and they can’t help but keep cutting more and more and more, exposing her body as they peel away layers. Many of the men laugh as they do so, their faces mostly cut out of frame. Though it is Ono’s eyes we watch as they fearfully stare at the people picking up the blades, the dehumanisation she’s subjected to is palpable. On several occasions, she was left fully naked by the end of the piece. As a modern day viewer, you push yourself to keep watching until the end. You force yourself to see the extent of human cruelty when it’s told it won’t be punished.

“Instead of giving the audience what the artist chooses to give, the artist gives what the audience chooses to take” - Yoko Ono

As her inspirations for Cut Piece, Ono cited Buddhist teachings of peace and giving. She was part of the 60s Fluxus art movement, widening the capacity of what we see art to be to bring it to those outside of artistic circles, opening up the stage to performance, music, and object-work.

This is not to say that all women in art or in politics fell in step with one another. The body, control of it and surrender of it, are essential to the work of women in performance art. It is, often, their canvas, their paintbrush, their marble, their clay.

“Early on I felt that the mind was subject to the dynamics of its body. The body activating pulse of eye and stroke, the mark signifying event transferred from “actual” space to constructed space. And that it was essential to dance, to exercise before going to paint in order to see better: to bring the minds-eye alert and clear as the muscular relay of eye hand would be.” - Carolee Schneemann on her work

But many found this use of their body, often nude, and often with directly sexual implications, was rejected by third-wave feminists. Schneemann described a disconnect between herself and political activists, feeling they didn’t accept her methods or approach to liberation.

If performance art outside of the existing realm of the art work can bring power to those who are marginalised, how do we reckon with the priorities facing our societies? How does someone earning minimum wage, putting all of their energy into survival and that of their loved ones, find the time and capacity to create and be art? These aren’t new material conditions, and, arguably, with social media, we have more opportunities to be seen than ever. But living as an artist isn’t financially viable, particularly for those whose existence would stand to embody performance art the most. To be a creative without existing financial support, presently, you have to have a product to sell, or be willing to use their platform to advertise, which isn’t particularly compatible with art. I can’t imagine what it would have been like to watch Schneemann’s Meat Joy with a 30 second break in the middle for her to explain why she’s partnering with ASOS.

For this reason, those who live as artists are typically scorned as free-spirited offspring of the upper-middle class, who don’t understand the ‘real world’. This is a fair assumption, but the more we associate art with those who operate from a place of privilege, the less connected it can be with some of those who may need to create and engage with it the most.

It’s not a new perception, that art and performance art are somewhat gratuitous. Rhythm 0 was a response to widespread suggestions that performance art was attention-seeking and masochistic. Abramović put the progression of the piece and its outcome in the hands of ordinary people, and their response was to behave even more extremely than one could have predicted. She evidenced the necessity of performance art as a reflection. In this sense, performance art can further operate to raise the voices of those who often go un-believed.

Some claim that social media events or even whole personas are performance art, often jokingly. I’d suggest that doing something without full conviction- whatever the essential, material form of conviction might be- in a public space isn’t performance art, but still, fans of Trisha Paytas insist that’s what her videos are, alongside HRH Collection’s vicious car raves. It’s increasingly normal than ever to see into every aspect of a public figure’s life until they become their own brand, commodifying every aspect of their life. It appears that we’re more than happy to accept that everything they embody, too, could be a performance. Art? Not so much.

Performance art has both a lowered barrier to entry via the exposure of the internet, and simultaneously a higher threshold for impact. Everything we see is designed to astonish and surprise, because media markets are so saturated. Every TV show has to kill off main characters, every film has to end with a twist, every song has to sound entirely new and different. Before you even have your morning coffee you’ve probably seen twenty people people behave bizarrely on TikTok. How would an orchestrated, intentional art piece be more interesting than that?

It’s not a new suggestion that we’re numb to the truly shocking. Nothing could be more heart-wrenching and shocking than the real events we see portrayed in the news. Nothing could exemplify the desperate situations experienced by many across the world than the world more than the reality of them. It’s been years since a standard response to a news item became ‘we live in a dystopia’, and we’ve become deeply bored by it. The apocalypse is dull. Satirisation of a farce is nigh on impossible. Can we be surprised anymore? Can our perception be twisted by those attempting to do so through orchestrated art pieces more so than the unfiltered world around us?

One of the guiding principles of Abramović’s work is asceticism. Even in the preparation for recreating her works, she pushed her artists to the limits.

“I have to be very strict and rigorous. We bring [the artists] to a place in the countryside and train—I’ll give you one example: opening and closing doors as slowly as possible for three hours. When you do that repetitively, at some point, the door is not a door anymore. It’s a kind of opening of the mind, of the universe; it is completely transformed into something else. You have to experience it, and to experience it, you have to do it—and you have to do it without food.” - Marina Abramović’ for Vogue (2023)

Is asceticism something most of us are capable of? Arguably not, in our world of overconsumption and product-driven media, our need for constant comfort. I suspect we’d also struggle to read an intentional frugality as authentic: if we’re assuming that many of those existing in the arts are those with the money to do so, a manufactured display of being a ‘have-not’ wouldn’t be particularly palatable, except perhaps to the ‘haves’- who, I’d suggest, don’t need any more superfluous markers of social intellectualism.

So theoretically, if performance art is more simply to perform, there isn’t technically an obstacle to engaging with it. Only a sense of disillusionment in its potential impact.

“Do you believe performance art is dying?

I don’t think so. I think that performance never dies, because every time we go into economic [and other forms of] instability, performance goes up. Every time they start selling at high prices, performance goes up. Performance doesn’t cost money.” - Marina Abramović for Vogue (2023)

To an extent, protest is performance art. The work of groups like Just Stop Oil, such as their famed soup-based vandalism of Van Gogh’s sunflowers to highlight our priorities of everything material over our natural word, comes to mind. Māori MPs in the New Zealand parliament performing a haka and tearing up a copy of a new bill that would undermine their rights as per a nearly two century old treaty. Perhaps its future lies in the emphasis on performance rather than art.

Or, perhaps not. In a society where performance is everything, where externalising an audience is a way of life and commodifying your day to day for social media is a lucrative career, in a society where visuals and appearances matter more than ever before because they could be captured at any moment, and because we have methods of altering every tiny aspect of how we look and portray ourselves, perhaps not performing is the most subversive thing to do. But how do you show people that you’re not performing without performing? Without recording? Is it about time we just lived? The category of performance art has always been a blurred one, but it’s increasingly wall-less, with peoples’ whole existences being seen as performance art.

“I thought art was a verb, rather than a noun.” - Yoko Ono

Is it performance art if you don’t know you’re doing it? Is your sixty-year-old neighbour who doesn’t wear makeup or know how Facebook works a performance artist? Well, no, not really. So we can agree that intention is part of the key to it all. Intention to reflect, disrupt, question, exemplify. But what if we don’t like the intentions behind the art?

Being ‘cancelled’ has become more and more profitable. As I see it, there are two types of figures who manage to turn cancellation into their brand and use it to their favour. There are trolls, edgelords, who will be satisfied with any level of disruption they manage to cause, and will always find a way to be above it. And there are martyrs, who will always see some respect for whatever act they’ve committed that’s allowed them to be cancelled, and will be propelled further because of it.

There is a function to this, whatever you want to call it; criticism, cancellation, ostracization. It operates a little like virus mutation: those whose platform can be quashed by the accusations slip away, those who can’t mutate, and future accusations can no longer hurt them. If anything, they make them stronger, and the point is proven. The likes of Russell Brand, who spent years laying the foundation for allegations about himself to come out by building a persona of someone who challenges the mainstream, and positioning himself as the voice of truth, come away from accusations with an even more devoted crowd. Not unscathed, but thriving in his exposure level, and, undoubtedly, still rich.

The other kind of ‘cancellations’ are those who parrot the rhetoric of opposing political forces as an attempt at ‘satirisation’, with the supposedly implicit underlying observation that they obviously don’t actually believe in it, they’re just demonstrating how extreme it is, and how extreme they should be able to be. I’m referring to the dirtbag ‘anti-woke’ left, the Red Scares and the Honor Levys of the world, whose attempts at nuance have little room for empathy towards those most affected by socio-political structures. An approach to politics heavily based in podcasts as a form of media that can, to an extent, exist in a vacuum.

This is often likened to performance art, in that the very existence and persistence of these people demonstrates something about our society (or so we’re told). They don’t actually subscribe to the beliefs they parrot in their triple platinum albums, their bestselling autobiographies, their hit tweets and viral interviews. They’re actually just ‘playing a character’. A character who provides a space for those bigoted views to be expressed and reinforced, who empowers those who genuinely hold those views, but a character nonetheless- supposedly.

Lucie Eleanor wrote insightfully about problematic faves in her piece, ‘edgelordism’. She discusses a dilemma we’ve surely all faced: how do you respond when someone whose art you value turns out to be disappointing?

“I think we should listen beyond the irony. When Matty Healy sings, “Because I’m a racist,” what if we just believed him? Why are we so desperate not to?” - Lucie Eleanor for sublime miscellany

I couldn’t agree more. I’m bored of trying to figure out whether I’m looking at the mask or the face behind it. Not sarcasm, not true satire, but a game of cat and mouse. The appreciation of depth in art comes from unpicking its layers, its value, its place to the creator and where it sits with you. This is nigh on impossible with edgelords, who, for a while, I truly thought we’d left in 2014. I want rich, genuine, sincere art, not a hall of mirrors.

The observation that sensitivity and refusal to observe anything outside of your own experiences and beliefs is dangerous is a fair one, though the people the dirtbag left views as being the main perpetrators of this may be misguided, and their methods harmful. In her Vogue interview, Abramović vocalised something similar for the context of performance art.

“We’re talking a different time. We’re talking political correctness. [There are] so many restrictions on all works now, not just me. Performance artists in the ’70s, not one of their pieces would be possible today. Museums would forbid it. The security would forbid it. There would be a huge riot in the media about how appropriate [it was] or wasn’t. You know, I am so fed up with the system right now, because artists have to have freedom of expression, and this has been taken from us.” - Marina Abramović for Vogue (2023)

I’m going to surprise even myself when I say this, but I don’t agree with her. The people of London and its many tourists from around the world did travel to see her exhibition. The most awkward of Brits sidestepped between the exposed genitals that guarded the second half of the show. Guardian readers everywhere discussed how much they liked it at their dinner parties. The quotes from Abramović that I’m using are from her Vogue interview- would someone whose work is viewed as having no place in society be interviewed in Vogue? Art galleries and many artists may not be thriving financially, but art still remains a huge part of our lives, and there is a continued hunger for it. To deny that, or to suggest that it’s ‘political correctness’ that restricts the potential for artists to flourish, is, to me, incongruent with the reality of the situation.

In the 70s, Abramović’s art was being censored because, amongst other factors, she was a woman. When Carolee Schneemann was studying art in her youth, she was told the class could only host male life models, because the female nude body was inherently inappropriate; she resorted to displaying and drawing her own form, and was consequently expelled. In 1968, Valie Export walked around Munich with a box held in front of her, for her piece Tap and Touch Cinema. She invited passers by to reach into the box through its curtains, and touch her naked body for up to thirty seconds. When Milo Moiré did the same in London in 2016 to echo Export’s original message about women’s ownership of their bodies and right not to be touched, she was arrested. To suggest that there’s been a direct switch, and that it’s those with modernising beliefs who are trying to extinguish the flame of shocking art, is clearly at odds with the continuation of these factors.

It seems to be less that political correctness wants to sanitise art- although the rise of purity culture is concerning, as we grapple with what to do about an increasingly online younger generation- and more that the right want to do so. Books are banned, drag artists are harassed, journalists, academics, and celebrities are being fired for speaking up about the genocide in Palestine. These attempts to silence aren’t the actions of the ‘woke mob’, these are the actions of those desperate to use their power to suppress. This is, of course, a huge generalisation for the sake of exploring this topic, in that there are many on the left who are falling short in their ability to engage with the reality of the world and alternative opinions. But just because art exhibitions now typically include content warnings- often for those who’ve been so busy living the reality of the difficult topics discussed that they’re too tired to spend their Saturday afternoon looking at them in a gallery- doesn’t mean that it’s attempts at progress that are thwarting the persistence of performance art.

Perhaps the dirtbag left or the satirical right, the Americana-obsessed or the old money aesthetic-seeking are, in their own way, expressing what they believe to be a form of performance. It comes down to whether we measure art in existence or impact. I think art can and should be measured by its own merit, and has value even without being seen or understood. But if you’re going to base your whole personality off of being provocative and inciting conversation, you clearly care about impact, no? This is where performance art has its strength: an ephemeral piece demonstrating visceral meaning, an episode, a temporary engagement. To me, the satirical persona is a cop out, the ‘bit’ is an excuse, and doesn’t capture the essence of satire at all: to embody the depth of something in art is almost identical to it being your reality.

At least this is a more understandable use of hyper-irony. Often, whole individuals’ platforms are sustained by projecting an uncaring approach to issues, defending a right to absence, functioning only to represent a rebellion- against what exactly? We’re seeing artists and content creators rise to fame, whose only message is that they can’t be cancelled. No matter how hard you want to try. They invite you to critique them, to prove your own sensitivity, then claim to have never really believed in what they were saying in the first place. They stand for nothing. It’s a waste of life, to prove that you can say whatever you want, without ever saying anything that you particularly want to say.

Free speech is vital, and is worth fighting for, but when one attempts to prove this by saying things they don’t care about or believe, the message of this importance is degraded. So much of the internet space, and particularly that of artistic spaces, serves only to be anti-anti. A double negative. It cancels itself out into non-existence. It feeds the dystopia machine. As a movement, it bores.

The performance art pieces I’ve explored in this essay have had clear, high stakes. There was no level of irony in Ana Mendieta’s Siluetas, no tongue-in-cheek quality to Cut Piece. These women were willing to engage with the genuine threats they and their communities faced (and still face) every day with sincerity and brutal vulnerability. And, often, with danger. The morning after staging Rhythm 0, part of Abramović’s hair had turned grey.

This isn’t to say that everyone has to achieve political effect in the same way. Satire and parody have been political tools for a long time, but until now, they haven’t tended to make fun of everything. To belittle and render unimpactful everything around you, nihilism that’s so often tinged with privilege. The idea that just anyone can afford not to care, and can take pride in demonstrating to you how little they care, about the socio-political world around them, contravenes what these original artists risked their safety for, and does so under the guise of performance. Art predicated on and inspired by a ferocious lack of empathy is not art. Even if they claim irony or that ‘you just don’t get it’. If you’re searching desperately for meaning and finding only rolling eyes, your instincts are probably right. When the conviction to demonstrate how pointless everything is has won, what will we be left with?

If you claim something as part of your identity, there’s no explaining it away as an act. You can still create things that are meaningful, valuable, impactful, you can change and fluctuate as an artist and a person, but all of that will only be interesting if you do it with a shred of all-evasive self behind you.

This isn’t to say that performance art doesn’t have a place in our present world, but our standards of what constitutes it have to change. Someone publicly sharing their views and behaviours with a supposed element of irony is not performance art, it’s not a social experiment.

The punch of previous works of performance art is going nowhere. We can access that any time, regardless of what continues to be created. We can lean on the artists, particularly the women, who led the movement through the 60s and 70s and know that their work hasn’t lost impact. Creating new, relevant performance art is a different story.

“Performance is really changing forms. There’s so much more interesting stuff right now: how performance is interested in science and technology, how performance is interested in music. There’s lots of merging activities and interests. I think it’s always exciting. I am very much looking at what the new generation is doing with open eyes.” - Marina Abramović for Vogue (2023)

If we can create space and an audience for those who genuinely want to use their voice and their art to harness a message they care about, maybe we can get there. Perhaps performance art needs no longer occupy a space more extreme than what we see in our reality, as it appears there isn’t anything more extreme. Perhaps instead, it continues to distil our forgotten humanness. Our need for connection. The challenge is to not belittle the place that art has in our society, in our political movements, but instead to champion it for generations to come. If we can find a way to access that vitality without undermining the genuine experiences of those whose voices could be uplifted, if we can operate with sincerity and reach into one another through innovative mediums, performance art can find its place in the now, in the fleeting, and in the years to come.

angelic dissent has a backlog of over 40 essays, all completely free to read! if you enjoyed this and want to support me to be able to keep writing, you can buy me a coffee here :)

if you enjoyed this essay, you might like my piece the artists who raised me, about the inextricable link between art and identity.

wonderful as always, probably my favorite of the series and a delightful read. performance art is in a really weird state these days

ive been thinking about this for days & had an hour long discussion about it with friends last night—this whole series was so thought provoking & thorough !