This essay is part one of Digitally Altar-ed, a four-part series dissecting the elements of art, social media, and collective consciousness that we choose to worship in the all-consuming digital realm. Each essay can be read independently, but together they capture a growing, dangerously misplaced idolatry driven by our engagement with the internet. You can read the other pieces here when released and subscribe to receive them in your inbox.

We’re trapped in an advertising hall of mirrors. Images for sale everywhere we look, unable to judge what’s real and what’s not. Nowhere is safe. The ad campaign is officially cemented as another medium to be appreciated in its intricacies. Whether we’re praising the creative vision or enjoying a brand positioning themselves as relatable, it’s increasingly difficult to tell the difference between typical internet content and adverts. Or is there a difference anymore? And the message I’m seeing, reading between the lines, is that I’m supposed to thank the brands that are bombarding me.

It’s one thing when we’re looking at marketing for art. It’s Zendaya wearing red carpet outfits that correspond with the film she’s starring in. It’s intentionally obvious public interactions with celebrities like the one between Bruno Mars and Lady Gaga before the release of their song, ‘Die with a Smile’, or the one between Bruno Mars and Rosé before the release of their song, ‘APT’. It’s anyone who’s anyone being pictured with a copy of Intermezzo before its release. It’s creative flyers for club nights and DJ sets plastered on lampposts. And if you haven’t read some analysis of the beauty in the brat campaign, you’ve managed an incredible feat.

Using our obsession with celebrity culture and gossip to garner streams feels more forgivable, in that we’re actually being entertained. Here, the marketing actively feeds into the experience of the product, at least. Particularly in a world of on-demand entertainment, there’s something fun about being excited for a new book to come out, showing up at the cinema on a film’s first showing, or hosting an album listening party. We’re brought together, and closer to our passions. But the same isn’t true for products, particularly the ads we see on social media- and if it is, it’s a little concerning. The day people start holding Rhode Skin release parties- that aren’t for influencers to eat custom cupcakes at- maybe I’ll change my opinion.

It’s not that I don’t think marketing requires talent- of course it does. It takes huge skill to be able to understand the market and the consumer’s relationship with it, to innovate new ways of tying the two. If we were to dismiss marketing as being skill-less, we would be accepting that we are really, truly, that easy. That we can be convinced by very little. Choosing the packaging and the audience and the angle can take years of experience. There’s (usually) more to it than choosing which TikTok star to #gift, and if that’s the only place you’re seeing an ad, the product probably isn’t very good. Although brands don’t seem to think so- influencer ad spend last year totalled £820 million, and consistently rises around 16% every year- in the US, it was around $4.3 billion.

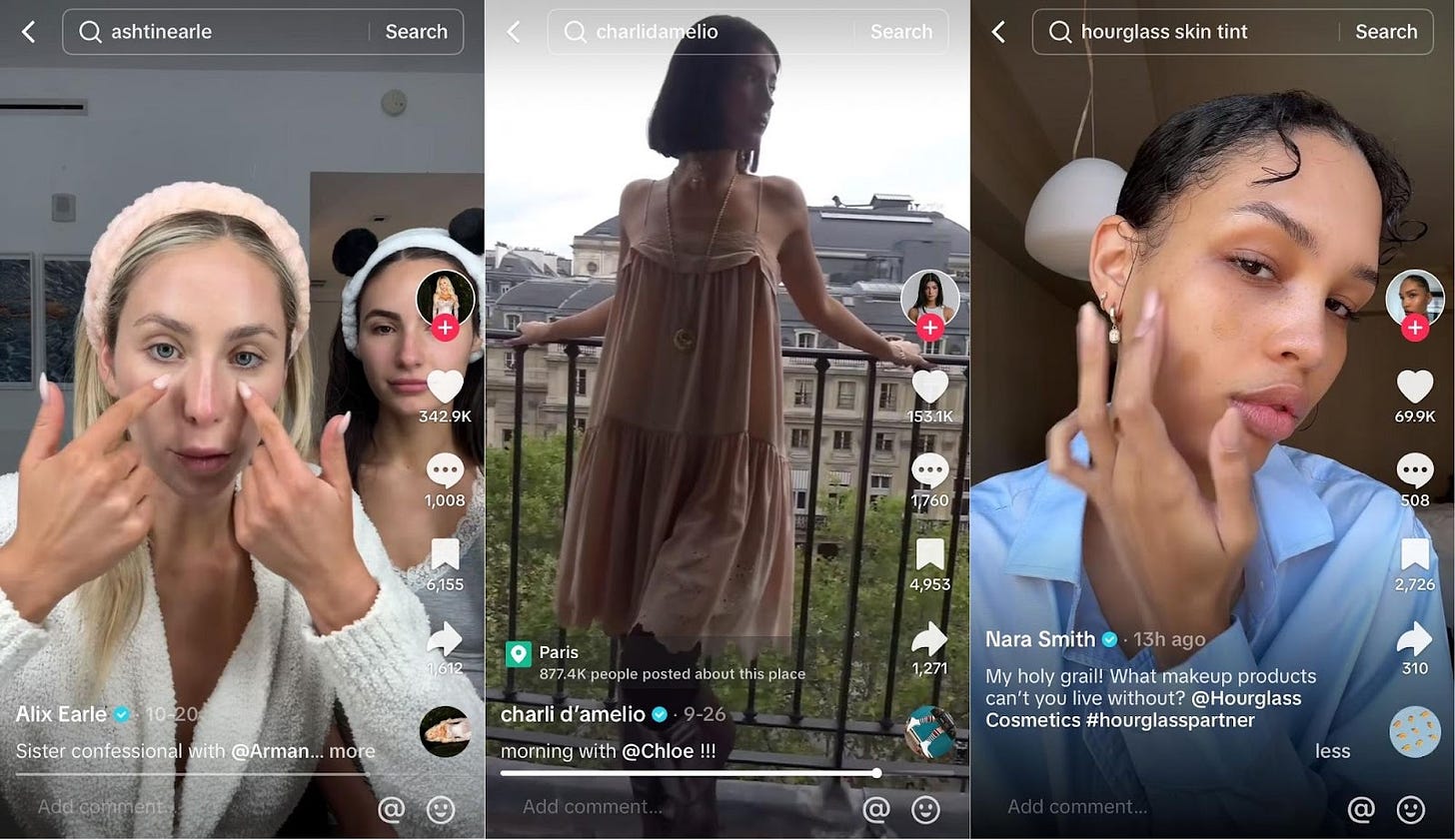

Selling products through influencers isn’t a new concept, since celebrities have been used to advertise things as long as there have been celebrities. But never before have brands been able to target such a specific audience, never before has just sending a product to someone in the hopes that it’s documented in one of the videos chronicling their day-to-day, been such an effective technique. Influencer marketing, in a very simplified model, operates based on René Girard’s principle of mimetic desire. This is the idea that if human beings see someone else with something- particularly someone else with prestige- they want it themselves. The more trustworthy this role model seems, the more influenced we are. But so too is the truth that the better they are at painting this product as being the secret to their success, the core of their identity, the more influenced we are. And since the internet is a training ground for identifying with the media you care about and the objects you own, it’s an easy currency.

The lives we have around us to observe, the closest look at anyone’s daily activities we have, are usually the people in our phone more so than those we know personally. It’s the people who live in huge New York apartments, wear exclusively athleisure matching sets, and only have to mention something in a video to be sent a lifetime supply. I’m not sure many people would turn that life down if it was offered to them. But we have to know that most of us can’t replicate that level of consumerism in our own lives, that the level of spending (and spare time) demonstrated to us the most is the least accessible. This was articulated masterfully by

at in her recent essay ‘is everyone richer than me?’. She eloquently captured the obviously unattainable yet seemingly omnipresent display of wealth we see from influencers and even peers.“Everyone, of course, also magically happens to have enough free time and resources to pursue creative projects without a full-time job. Scrolling has become a scavenger hunt for truth: why are you at a workshop at 3 pm on a Tuesday? Pilates on a Wednesday morning? Your life seems so fun and devoid of obligation. I love it.. and I want it.. but I don’t have it.. and I’m not sure I can have it any time soon.”

- is everyone richer than me? by

for

We can’t access their lifestyle, but maybe we can afford the matcha powder they use, the personalised supplements, the hair straighteners that were free for them but would be half a paycheck for us. We have to remember that for most of us the hottest brands aren’t all that relevant, because unlike influencers, we’re not selling them. In his theory of mimetic desire, Girard highlighted that the objects of our desire aren’t based on our taste, but instead our societal ideals- or, perhaps, that our taste isn’t based on our own personal preferences. It’s the owner that imbues an object with value, and so to own it is to become closer to them.

And it’s true, the shape of the market does reflect the shape of our society, as do the fashion trends that people are favouring, the horror tropes at the top of our watchlist, the ways we’re spending our free time. But the latter examples, though connected to marketing, are artistic and interpersonal, shine light on the priorities of the zeitgeist via our own participation in the world. Whereas (and I don’t mean to sound hyperbolic here) adverts are the devil.

It turns out I’m not alone thinking along these lines: 88% of those under the age of 28 reported being “de-influenced”- not buying something because they’d seen it advertised on social media. Pretty powerful for a generation that is typically assumed to be digitally-obsessed. Reasons cited included being so over overconsumption for the sake of the planet, as well as lack of trust in influencers. This makes sense when you can’t tell what’s an Instagram post and what’s an ad, a continued conversation on a podcast and an ad, a genuine recommendation and an ad. It makes sense when referring to items by their brand name rather than the name of the object (Dyson, Bala bangles, even iPhone) is the norm. At this point, there isn’t much difference. I’m sure some prefer ads to seamlessly blend into the aestheticism of the content they consume rather than being discrete and therefore less palatable, but it’s how easy it is to take in hundreds of ads in a day without realising it that’s infuriating me. It renders so much of the creative, entertaining, or plain distracting works I want to engage with disingenuous. It’s naïve to assume that any product you’re being shown, even if not in a directly paid ad, isn’t somehow operating as part of a business model. The company is the new church and there’s no state separation. Nothing is sacred.

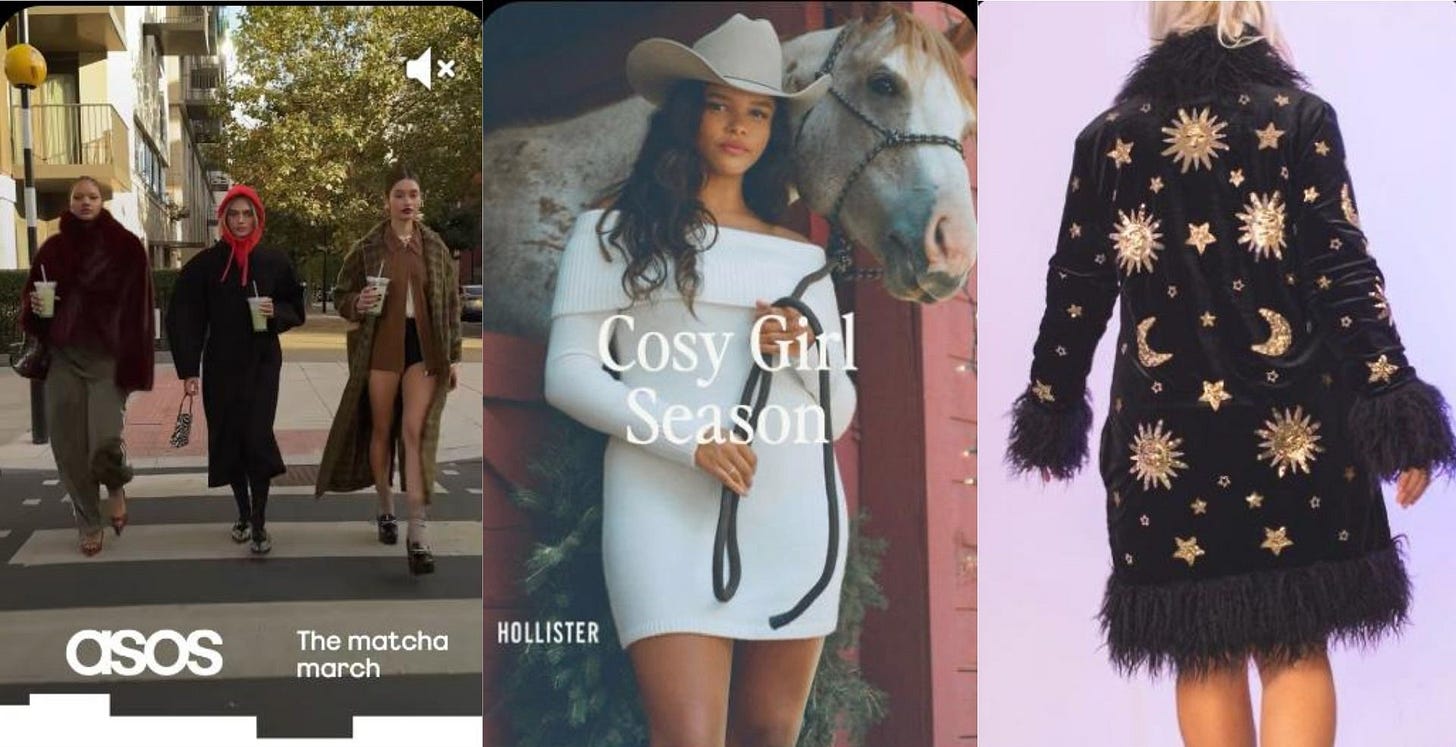

Despite the theoretical specificity of the algorithm, specific brands advertised by specific channels become ubiquitous. Audible, Better Help, Grammarly. What happened to Best Fiends? Anyone? Pinterest is essentially unusable these days. When I use the app recently, around 45% of the posts are ads, even if they don’t look like it. I try to look for a cocktail recipe and am met with an ad for an Etsy spell that will make my “love dreams come true” (reduced to just £150!). I look at a photo of a nice outfit and am given ten different options of similar dresses I can order right now. I didn’t realise that even shopping had a soul until it was gone.

In the same way that reading Twitter helps us feel as though we’re up to date with the culture, seeing ads makes us feel as though we’re in the loop with the market, as though that’s of any use at all. Unless you specifically plan to seek out a product that you’ve been enlightened to the existence of through an ad, you, the consumer, don’t really gain anything, but it’s central to the ads you’re shown that you see a product as an essential part of the person you’re trying to be, or as a way to show yourself love. It’s a fallacy to think that more exciting, engaging marketing campaigns linearly relate to the quality of a product. Social media ads for greens powders and vitamin gummies and a red light mask that might improve your life by half a percent at most, for a month or two, in exchange for £99 (plus shipping).

It’s a little like one of the key driving forces of how marketing operates today: cigarettes. Through the 50s and 60s, different brands would display competing claims about one another, despite all being pretty much the same (and each just as bad for you as the next). This meant the only way to compete was in price, and in positioning of the buyer. Lucky Strikes were for those wanting to lose weight, Camels were for refined women, Marlborough’s were smoked by the most manly of men. Many of the products we see today mirror this in that there’s very little difference. Even when it comes to quality, in clothes for example, there’s often minimal correlation between price and longevity, fairness of labour practices, climate impact. Companies (and influencers) make money based upon what they can tell you you’ll be when you buy their product.

"Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others in order to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires." - René Girard, social philosopher (1923-2015)

And the more you interact, the more sell-to-able you are. Nearly a decade ago, a landmark study by Stillwell et al. (key player at the since-scandalised Cambridge Analytica) found that within 10 Facebook likes, the algorithm can predict you- knows you- better than the average colleague. Where likes demonstrate your interest, your interests demonstrate your personality traits, and your personality traits can predict your behaviour, that makes your activity online hugely valuable. By 50 likes, it was found that Facebook knew you better than a friend or flatmate. For the site to predict your behaviour and tastes better than your partner, all you have to do is like 300 posts. I’m sure I don’t need to emphasise that if this was the case 9 years ago, the algorithm, particularly given how social media advertising is central to the profits of many industries, will be infinitely more advanced by now.

This makes the main space that many of us spend our time- the internet- a playground for advertising. Almost 80% of ad spend in the UK in 2023 was on social media, that itself an 80% increase from 2020. In fact, there aren’t many places you can’t see ads. AI generated word salad on the side of a bus stop that tells you nothing about a product but reminds you it exists, at least. I understand that advertising has to continue to happen and there’s very little we can do. I also understand that that’s how product design works. Though I don’t think we particularly need many more variations of the same product, it’s clear that’s still going to happen. Where I draw the line is endorsing adverts like they’re art.

And it’s women who have the most purchasing power, given that every aspect of our lives is commodified and sold back to us more so than men. That’s not to say that men don’t have a huge part to play in reducing overconsumption, but since the products being marketed to women apply to more everyday items (make up, clothes, skincare, even home goods), particularly that would be used in, for example, a ‘day in my life vlog’ or ‘morning routine’, it’s easier for this blurred-line advertising to operate. Additionally, since many of the products marketed at women are intended to be a ‘cure’ for some deficiency, it’s easier to see the brand polluting your feed as doing you a favour. Let’s be clear: you are a commodity to everyone at every step of the chain, from the influencer on your feed, to the social media company who platforms them, to the brand who pays them to advertise.

When we collectively appreciate how well the advertising operates, we do the job for those who make money off of us. To be marketed to is to be manipulated, some of us agree. But we don’t seem to mind. We know the products won’t make much of a difference to our lives, the most we’ll see will be a dent in our bank accounts and our carbon footprints. And yet we laud how well they convinced us that it was the latest must-have, how much more fresh and exciting it is than other ads of its kind. I understand that many businesses exist to fulfil a vision, but so much of the advertising we see is for entirely unnecessary products. I don’t mean unnecessary like new clothes or paintings hanging in your home or nice food are unnecessary- things that you only access when you have the money but, we can all agree, can enrich your life. I mean unnecessary like an oura ring to keep track of your heart rate, the newest mobile phone, different ground coffee to match who you really are, personalised hair care. That’s what we want to be creating art for?

To an extent, if working with brands allows artists who wouldn’t otherwise be able to support themselves to do so, it has its benefits. It would be nice if there wasn’t such a conclusion of futility, but what can you do? But that itself could be a jumping off point for us to appreciate their craft and be reminded of just how much art can make us feel. If a billboard evokes emotion in us, how incredible must that feeling be without a sales agenda?

And yes, if the definition of art is an expression of creativity, something stimulating, then perhaps you could see ads as fitting into that. But many of us have no issue understanding why AI-created art- arguably an expression of imagination, often stimulating to observe- isn’t quite art as we know it. Art has to have soul. If your creative outlet is making someone else money with very little benefit to the consumer, I don’t see much soul there. That’s not a measurement of how worthwhile it is or how good someone can be at it, I just don’t think we need to thank those who manage to convince us we’ve been waiting our whole lives to buy their product, just for creating an ad that we enjoyed.

We do have a tendency to see the beauty in vintage ads. Again, my view that ads aren’t art don’t make them less visually beautiful. But even these- or at least the ones we deem aesthetically pleasing enough to keep around- often follow the same pattern as influencer marketing: beautiful woman adjacent to product. We love images new and old of Times Square and Piccadilly Circus with their bright screens advertising Coca Cola and McDonalds; they’re iconic and speak to a long-since expired vision of the future. Spending time on any social media app is like walking through a never ending version of this, and we seem to have accepted that ads are part of our day-to-day experience.

The Pop Art movement was intended to act as a mirror to heightened levels of consumerism in the 50s and 60s, neither critiquing nor praising, typically, just highlighting by bringing products to the canvas. Part of the intention here was to indicate how the product was king, and in some senses, owned us more than we owned it. Now, that understanding seems to be so deeply ingrained in all of us, almost innate, embraced with eagerness or nihilism but nonetheless embraced. We grasp how central the product is to our life, and we ourselves have become the tools of promotion. It might be fair to assert that much of art is about making money- actors worth millions, musicians rivalling CEOs. Andy Warhol, perhaps the most famous artist in the pop art movement, was vocal about the fact that by creating highly consumable art he was engaging in business, and he was right. To prove his point for him, I’m not going to include an image- you probably already have a mental picture of his work.

There is also a lot of discussion centring the idea that the more commercial and sellable art is, the less soul there is anyway. You could argue that when art becomes highly valuable it is even more preposterous than appreciating the advertising of a product- an image exchanged for huge sums of money is ontologically stranger than a functional item being demonstrated. But where art can exist on any scale from a children’s drawing, a song made in someone’s garage, a twenty-something’s Substack, right up to the most prestigious monuments and tapestries and operas, marketing on the other hand is a single spectrum of measurement. How much money did it make? There is no other dimension on which it holds weight.

Art is art because it’s human, and because we can’t help ourselves from producing it. No force has ever been able to quash that drive. Marketing exists as long as a mass market exists, as long as social media exists, as long as the need to numb yourself from your day to day with a novel brand of pasta exists. But it doesn’t feel quite as set into who we are, not as painted on the cave walls as art does. The energy that we have to compare packaging trends or trend predictions, though sometimes interesting, could be better used figuring out what we actually like and why, or even if we need something in the first place.

It’s not that these things aren’t fun, and personally I still look forward to learning about innovative forms of marketing in that they represent the world around us-

and ’s newsletters are always fresh and engaging. But I’m trying to distil what I like about marketing campaigns aside from their selling power. If I like the photographer’s work, I look into their style and portfolio, their influences, their use of the visual. If I like the social message a brand’s attaching itself to, I research the issue itself. I do everything I can not to put the team behind the 500th iteration of oat milk development on a pedestal.I don’t want to spend my one wild and precious life shopping around to optimise every aspect of it, only to realise, at the end, that it wasn’t worth the energy. Maybe the product is going to keep its crown as a driving force in our life, but we need to maintain momentum around actual art as a practice, as a pillar, and as one of the few things we can do for ourselves that doesn’t have to involve money. We don’t need to worship the marketing campaign- we can let it worship us.

thank you so much for reading <3 if you enjoyed this and want to support me to be able to keep writing, you can buy me a coffee here :)

If you enjoyed this essay, you might like my piece ugliness is next to hotness, on the trend towards ‘weird fashion’ as a symbol of attractiveness (and my love for it).

oooooo i cannot wait to read the rest of these essays this is so exciting

Oh God, I love this. Marketing is not a bad thing when growing culture or the arts, but ever since TikTok, and especially following Covid, marketing for products has been insane. I rode that TikTok skincare era, but ever since I’ve come to understand sponsorships, it doesn’t feel authentic anymore. Thank God I’ve deleted TikTok now and the scam it poses. This was so enlightening, thank you for sharing :)