the artists who raised me

telling stories that aren’t mine so I can tell the one that is / in homage to home + sculptresses

My mum was an artist when she was younger. She doesn’t say it like that, she’ll tell you she went to art college and then did a fine art degree, and has pretty much never used it since. She’ll tell you she used to wear crazy clothes, Victorian nightgowns and culottes. She used to be vegetarian; she’d buy a lentil sausage roll and cycle home with it in the basket of her bike. She’d let her friends cut her hair and laugh at the kind of jokes people don’t make to her nowadays. The first person in her family to go to university. She comes from a kind family, soft-spoken and selfless, and you can see it in her DNA. I hope you can see it in mine.

At twenty-one, she wrote her dissertation about stained glass. When I was growing up, if I had a friend round, she’d help us stick together the simplest of star ornaments from colourful pieces of glass kept in the kitchen, in the cupboard under the boiler. Score the line, then break as though you’re not afraid it’s going to shatter in your hands. I loved the idea of her basking in blue and red and green, seeking out places where the sun would hit so she could appreciate it in all of its glory. When I went to Barcelona, and felt for a moment like I might understand religion in the Segrada Familia, I thought of my mum, who had insisted I make the visit. How did she feel in a place where the colours of the glass bled out way beyond their territory, inescapable haloes of vividity. It was as she’d hoped, wasn’t it?

The place I grew up isn’t too far at all from where she did, from where she went to art college and made lifelong friendships. That place is also not too far, at all, from where David Hockney grew up and went to college. Of course, he gave a decent chunk of his life to LA, where he painted pink tiled pools and creaking palm trees. No disrespect intended: if I see A Bigger Splash one more time I might scream, but I keep going to the Tate Britain anyway.

Aged 84, he’s back in Yorkshire now, where he should be. Digitally printing trees and fields in vibrant colours, more vibrant then when he worked with physical paint. An iPad artist whose work still captures hearts across the globe. Seems to be making art for the fun of it, and the money it sells for is incidental. Isn’t that the dream?

When she was a teenager at art college, my Mum had a school friend who chose Hockney as the centre of her project. As luck would have it, he was visiting nearby- understandable, given how central he is to the art scene (if you can call it that) in West Yorkshire. She knew she had to speak to him, to get an exclusive quote from the man himself. He was swarmed with people, an international local celebrity, always on his way somewhere, and her chances were low. But she was determined.

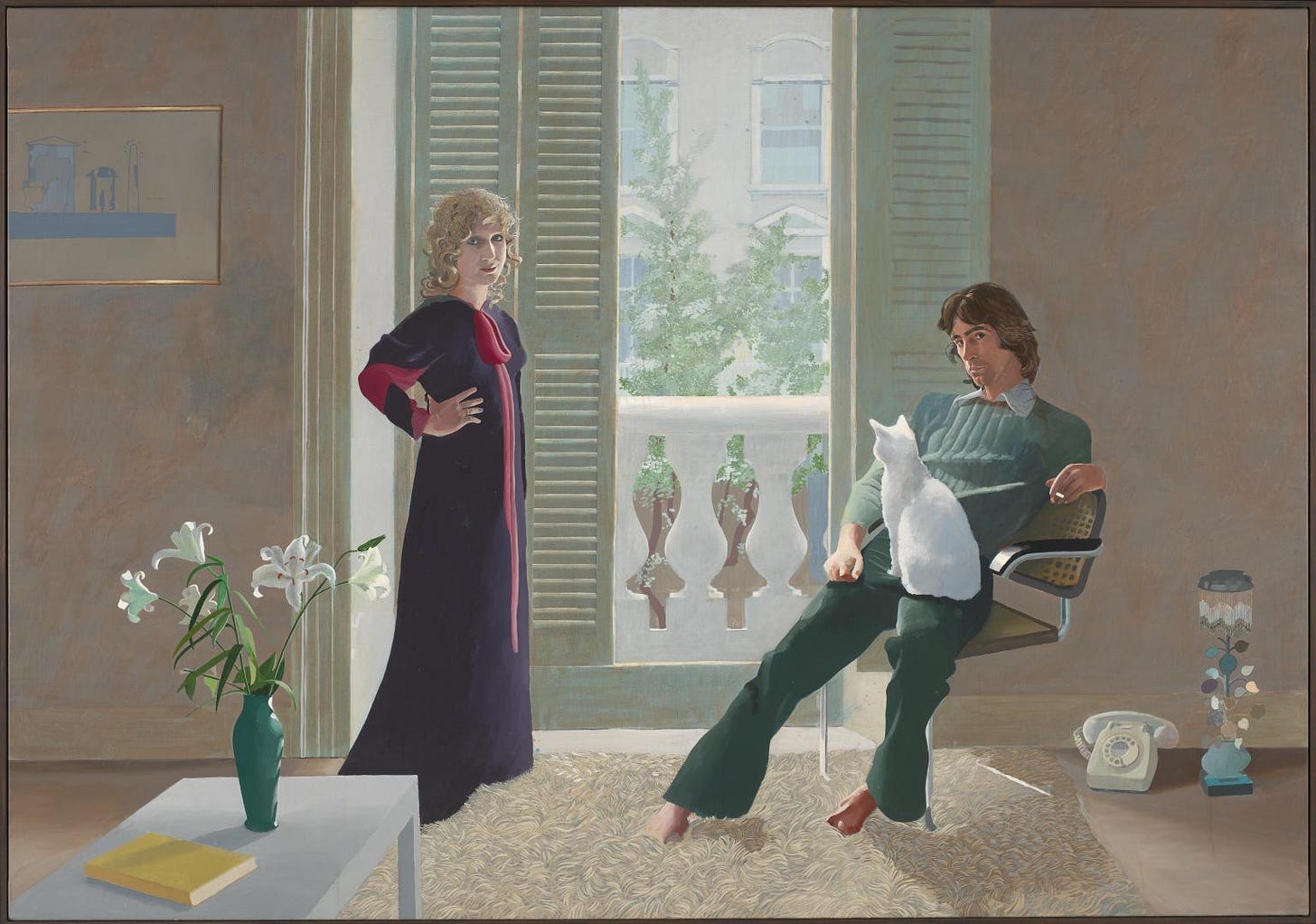

She managed to catch him in a moment of quiet, knowing she had a minute, maybe less. She didn’t ask for explanations or scoops on future pieces. She asked about what was already concrete. She asked what he’d change in his painting Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, if he could change anything.

He paused for a moment, thoughtful. Presumably wanting to give this schoolgirl the best answer he could think of. Then he said, simply:

“I’d make the telephone blue.”

Everyone I grew up with is buying houses near where we went to school, getting married. It looks like a nice life, living up the road from your parents, raising kids there maybe. When I was younger and I thought about a future in my hometown, sometimes I would experience the very distinct sensation that there was a plastic bag over my head.

David Hockney’s blue/not blue phone- that isn’t my story to tell. I’m too many degrees removed for ownership (as is the best place to be when it comes to storytelling). But what is mine to divulge is that I always thought I couldn’t do it: putting something out into the world, wax sealed, encased in Perspex, never being asked what I would’ve done differently. Let me prize off the glass every year and layer back into it, let me into your well thumbed copy to scribble over the ending, let me layer the harmonies to high heaven.

I’m not too bad at killing my darlings, I don’t think. Lining up the paragraphs, even whole pieces of work that shouldn’t see the light of day, for the slaughter. Keeping them penned in for my eyes only, in case they become useful for parts. But what if they’re all darlings? One day I’ll look back on the words I’m writing now and feel what, pride? Regret? Frustration? Nostalgia? The aim isn’t for them to be good enough to be seen, it’s for them to exist.

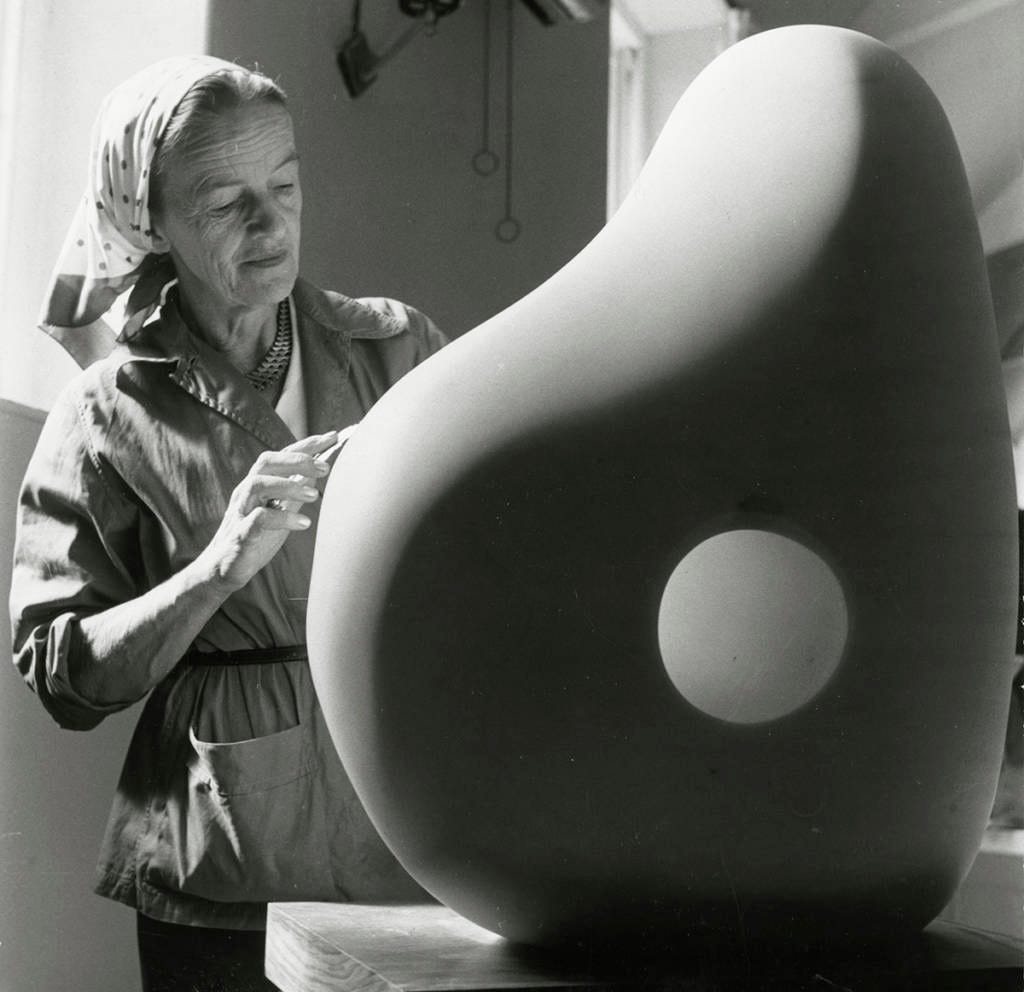

You gain an extra dimension when you operate through art. It can be a portal, if you let it. As a child I spent many Saturday afternoons looking at my parents through the circular holes in Barbara Hepworth’s The Family of Man. A collection of bronze sculptures, stacks of boxes, different dimensions to each, set into a huge plot of land turned sculpture park. It’s one of the key pieces she made not long before her death in 1975. They represent a group of people- a family. We used to line up next to whichever we thought was like us; I was always the smallest, of course. The last time I visited home, already halfway through writing this piece, we visited the sculpture; a place I haven’t been in years. The park is full of rhododendrons in this season, all colour, all bloom. My parents revealed something I know they must have said before, that I must have managed to forget.

‘Me and your Dad had our first kiss there.’ My Mum points beyond the sculpture, close to a car park. I blink at her.

‘There?’

What does it say that something so magnitudinal happened steps away from somewhere I was already feeling significantly enough about to pour my heart out? Did that feeling ripple back in time and change the reality? That the site had been where their love had started. And I think I know a thing or two about first kisses, and I think that’s the most beautiful thing I’ve ever heard, and I think I might cry a little on this sunny day where the grass looks slightly too green and the sky too blue.

So much of Barbara’s work is heralded in West Yorkshire, our shared point of origin. She’s built into the landscape of it, as was her dream; buildings erected to house her legacy. She always thought her art should be “allowed to breathe” in the fresh air. But despite her loyalty to home, Hepworth moved to London in her youth to study art, and later to Cornwall to raise her children, where she found inspiration in the landscape.

A lot of her sculpture work is characterised by smooth, gliding shapes, with single holes through the middle. Geometric weight, colourless presence to blame for the buzzing between her work and its viewers, the buzzing of the city. Strings between adjacent sweeps of Serravezza marble, Burmese wood, pristine alabaster mirrored her tension with her surroundings; the rise and fall of the sea beyond the cliffs in her St Ives life. But the holes in her work themselves were connections too- not absences, but expressions of space. Intangible mass. She understands, and explains to us through the plains of her sculptures, that time, form, are not just three-dimensional. In a Jungian sense, to which Hepworth’s philosophies leaned somewhat, what’s in the space between us irrelevant. The meaning is in the human need to figure out what’s there, through the hole and on the other side.

Now I can levitate towards her work in a building full of art. I feel a pull to the smooth surfaces, roundness of the carving, the portals back to my childhood. I didn’t know, back then, that the holes in her work weren’t just shimmering gateways to frame my parents in; I’d spend the rest of my life looking through them and feeling myself shrink at the small end of the telescope. From London, going to Paris was cheaper for Barbara. She would visit the galleries there instead of her hometown, see the world through eyes that would always ground the art with a tinge of her origin. For Hepworth, life and art were inextricable, one and the same, neither trying to imitate but instead embody one another. Barbara left West Yorkshire for London to find a bigger life, maybe it’s okay that I did too.

“Perhaps what one wants to say is formed in childhood and the rest of one’s life is spent trying to say it. I know that all I felt during the early years of my life in Yorkshire is dynamic and constant in my life today.” - Hepworth

Barbara was a close friend, contemporary, and even housemate of Henry Moore, another artistic branch of the tree. He grew up in the birthplace of my Mum’s side of the family, back when it was an active mining community rather than just another town covered in a sheen of useless coal dust. Their impact in modernism is only rivalled by their impact in the local area. A treasured mythology- my Grandad was part of the team who wired and electrified the Henry Moore museum in Leeds. Since I learned this, I’ve always associated the two. Moore’s charcoal sketches of tube stations being used as bomb shelters will forever evoke the shadow of the poplar trees that grew behind my Grandad’s bungalow, his striking lead forms bring the feeling of running my hand over my Gran’s ornaments. Moore’s sculptures are very similar to Hepworth’s, often described as more masculine for their bulk, width, and less coherent undulations. A common feature of his: unlike Hepworth’s complete, spherical bodies, his track peaks- apexes that never quite meet me another. Two points so close a breathe would be enough to entwine them, too solid to ever touch. Moore’s rough, humanoid bronzes are more nature than they are people, in a lot of ways. Rocky skin, crag joints, seated figures that invite you to perch on them, hide in them, bridging the landscape and the viewer. I always wanted to sink back and be enveloped in the blue-green. I wanted to be one with the ground so I couldn’t leave.

Every summer I listen to Corinne Bailey Rae’s first album on repeat, to remind myself of warm days in the passenger seat of my Mum’s car with the windows down. Smooth, swaying vocals with an audible smile and acoustic lilt, whole body sinking back into the seat. Golden, endless afternoons. If you’re familiar enough with it, you can hear in her voice that she came from Leeds, where I’d catch a short train to spend weekends feeling like maybe I finally belonged in the real world when I turned 16. When I saw her speak at an album release event last year, I felt my heart sink a little at how strong her accent still is. Not as strong as the people I know who still live there, but persistent and beautiful. It made me a little homesick. I don’t really have an accent. It’s not on purpose; I sit somewhere between the heightened vowels of the South and the deep, blunt Northern versions. I don’t get to claim that home the way others do, because I left it- maybe because I was always going to.

Recently I’ve been carrying around a digital camera and a film camera at the same time, alternating them with my phone. I don’t know what I’m trying to access with the collection of styles; the photos I’m taking don’t exactly resemble my childhood. But it feels good to collect all of the options. I’m not just trying to feel like I used to, I’m trying to see through the lens of Before, turning my periphery into a bronze portal.

It’s not that I want to go back. After years of surviving I’m now living, just maybe not as much in the present as I’d hope. There’s just something comforting about knowing that you came from somewhere, even if you’re not going back. We need to grow from the unchangeable, whether we’re tearing our roots from the ground or letting ourselves sink deeper into the soil. You can command all the hindsight in the world, but you can’t make the telephone blue.

Eve what a beautiful read, I am so happy I stumbled across your page on my feed as I am sure there are a lot more special pieces to come xx

I love this so much! everything in this piece is more vivid as a result your writing.